Think your story needs a visual boost? Follow along on how I'm shifting from writing novels and short stories to comics.

Have you ever had that moment of clarity when you realized that the story you're telling would be so much better if presented differently? That kind of realization can be both exciting and scary at the same time.

As someone who enjoys both writing and drawing, I always struggled with deciding which one to focus on. But in this case, I knew that a change was necessary for the story to truly shine.

Then I rekindled my thoughts to comics.

Comics combine both writing and art, but it is a distinct medium that requires a unique approach. To learn how to write them effectively, I read various graphic novels and several books on comic book writing.

This topic is for writers who have artistic skills and those who want to collaborate with artists. Not every story needs to be a novel to be successful or taken seriously.

To make the comic strong, it needs the foundation of the script to work.

What Is the Story?

Transitioning from novel writing to comics is a challenge for sure. Although the storytelling standards remain the same, the approach to writing is different. It is important to first establish the story before delving into the writing process, as the words may not flow as easily as they do in novel writing.

Discovery Phase

My project was to take a rejected short story from a few years ago and turn it into a comic. There is some attachment to this story but it’s more of a proof of concept: Can I turn this around in a more visual medium? Before I even thought of trying I asked myself these questions:

- Do I still love this idea? Am I passionate about it?

- Am I okay with spending at least 6 months working on this (and longer)?

- Will anyone else gain something from it (entertainment, assurance, etc)?

I was able to answer yes to these questions and I’m still working on it more than 6 months later. So now take what’s already written and outline it for the comic. If you haven’t started your draft yet, we can jump right into the terms you’ll need to know.

Comic Terms

Panel

The still image in sequence. The format or style is your choice. They can have borders or not, be long, short, wide, etc. This is where your descriptive tools as a writer come into play. There are more unique panel types such as:

- A Splash is a full-page panel

- A Spread is a double-page panel

- A Bleed is a panel that goes into the edge of the page

- There are more specific terms that go into the types of shots but the above are serviceable for right now.

I recommend reading the Art of Comic Book Writing for a more detailed guide on the types of panels and when to use them.

Lettering

The text on the pages of a comic.

Balloons

When creating dialogue in a panel, the speech bubbles should always point towards the speaker with a tail or thinker (if it's a thought). All the concepts of writing good dialogue apply, but you have more creative liberties to show the character's emotions through text. You can use bold text or another font to emphasize the speaker.

Caption

Used to narrate or give more context to a scene. Like panels, these can be with or without borders.

Outline the Beats

My original outline was a one-sentence summary of each story beat. Now the thinking goes from story beats to pages, and how many should each story beat take.

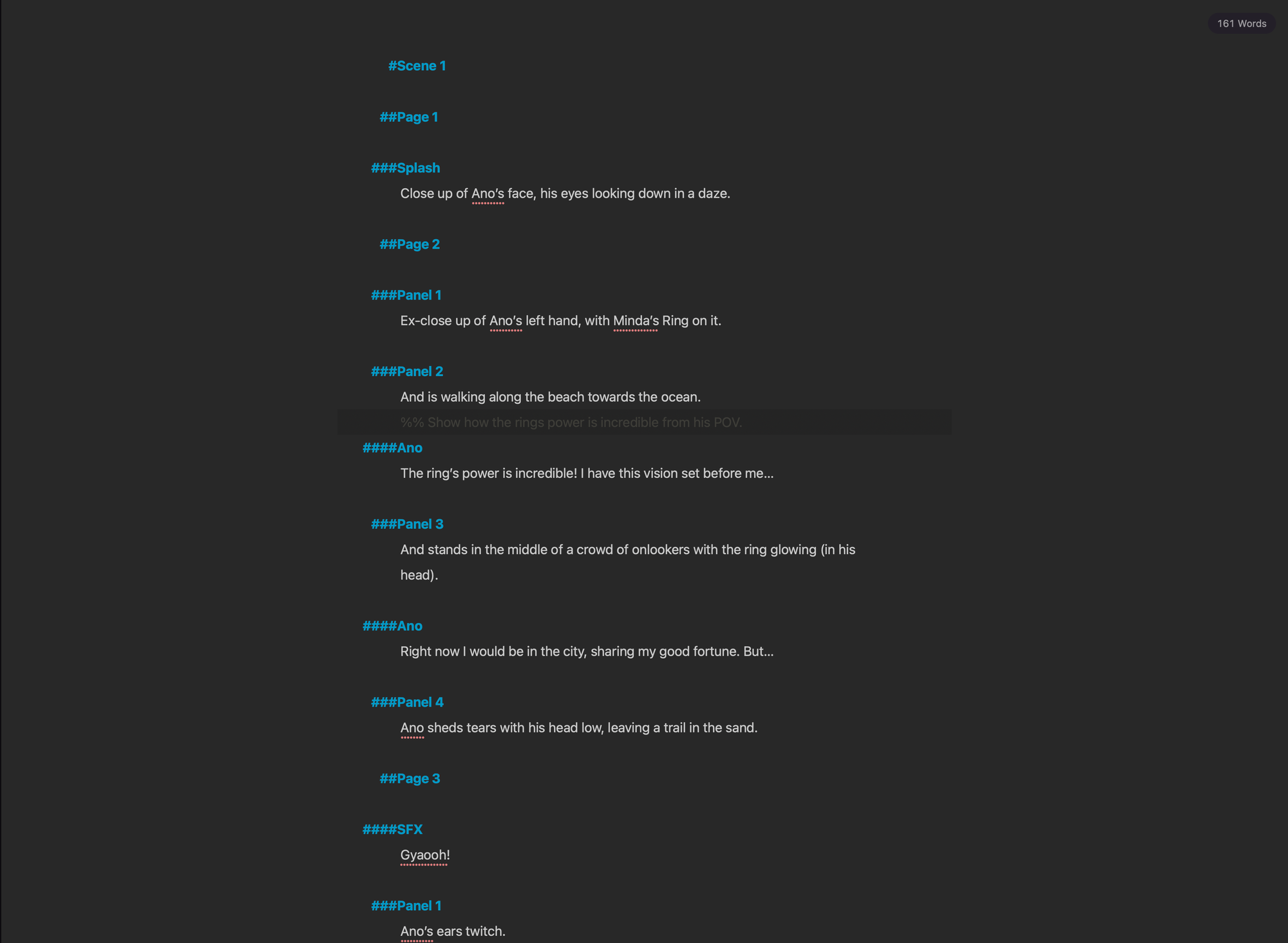

Depending on the page count for your story, the outline can be short and specific or long and broad. For Minda’s Ring, I was leaning towards the former. A typical issue for a comic is between 20 - 26 pages. So instead of beats, let’s go by Issue:

- Issue 1 - Ano’s father is ill and leaves one last request of his son, to finish his life’s work. Yet Ano has plans of his own.

- Issue 2 - To ease his own guilt, his fiancee convinced him to learn more about the Treasure of the Goddess. He meets a brash Captain of one of the world’s most well-crafted vessels.

- Issue 3 - Etc.

I have to stress that this isn’t how everyone does their script process, but it’s the one I find most helpful.

Character Driven is King

If you’ve written a novel before you’re already used to this mode of thinking. Character-driven stories are the most interesting because the character has agency and a desire of some kind. Ask yourself “why” and then answer until you get to the heart of what the character’s motivation is. What is the end goal? Their past? Their current situation? Keep asking until there’s nothing else to give up. I used Reimena Yee's Onion Method to go through this process.

Thinking Visually, Writing Visually

The visuals need to be descriptive enough, but not so detailed that there is no creative freedom. This is more the case if you are only writing the comic and not drawing it. Otherwise, if you’re doing both you can get away with more loose descriptions of the action in each panel.

Showing and Telling. Both are Good.

I’ve picked this up from many comics I’m reading. Long story short, there is a time and place for everything but you always want to show more than you tell. If you tell at all, it’s to enhance what is on the page. From Scott McCloud’s Making Comics, there are many ways to blend words and images together.

Use Your Words

This is another instance where writing good dialogue as a novelist comes in handy. All the tools that are useful when it comes to writing still apply in comics. This includes boring but important things like grammar, diction, and so on. The only time you’d deviate from these is for the sake of characterization.

Writing in Full Script

There are two “formal” styles of writing comics; Marvel Style and Full Script. Here’s what the differences are and why I’m going Full Script.

- Marvel Style - A general plot is given that may be collaborative with the artist and then the artist has full freedom to design the pages as they choose.

- Full Script - The writer writes a detailed script page-by-page and the artist follows the script.

I’ve read many artists who prefer Marvel Style up until they have to redo the artwork. The writer is also often the editor in this case and if they decide they don’t like what was drawn, the artist would have to redo entire pages that may have taken days or weeks to do.

What I’ve found is that limitations and structure enhance creativity. Too much freedom in Marvel Style seems to be a blessing and a curse. If you are both the writer and the artist it is less of an issue, but if I want to work with another writer or artist I need to take the workload into consideration for Marvel Style.

Test Run

Try writing out a script for a 10-page comic to see if you can get a feel of how to write one for yourself. Next week I will be practicing this myself on a very old piece of work as an experiment. So far I’m enjoying the flow of working between script and visuals and it definitely is the best of both worlds.